Ownership and Borrowing in Rust

December 1, 2025Ownership in rust is an amazing feature, it enables memory safety and it does it without the need of garbage collector. Ownership is mostly a way to manage memory. Other programming language can ensure memory management by using garbage collection.

In high level programming language like java or C#, we don't really need to worry about memory management as garbage collector does it for us.

Let's try to understand the pros and cons of garbage collector.

Pros:

- error free (no memory bug as garbage collector does this)

- faster write time (you can write programs faster as no need to deal with memories)

Cons:

- No control over memory

- Slower and unpredictable run time performance(cause we can't optimize memory and unpredictable cause the garbage collector can clean up anytime)

- larger program size (as garbage collector is also a piece of code that you gotta include)

Let's look at the manual Memory Management. In C/C++ you have to manually allocate or deallocate memory.

Pro:

- control over memory

- faster runtime

- smaller program size

Cons:

- error prone

- slower write time

But ownership model in rust is way different than all of these.

Pro:

- control over memory

- error free

- faster runtime

- smaller program size

Con:

- slower write time, learning curve(well we'll fight with borrow checker for sure)

In rust, we have some strict set of rules for memory management and if you break any ofthose then you'll get compile time error.

Stack is fixed size so it can't grow or shrink during runtime but heap can. During runtime a program has access to stack and heap both. Stack also creates stack frames which created for every function that executes.

Stack frame normally stores local variables of the function being executed. The size of the stack frame normally gets calculated during compile time. Which also means the variable inside stack frames must have knwon fixed size. And variable inside the stack frames lives as long as the stack frame lives.

Let's talk about heap. Heap can grow and shrink at runtime. Data stored in heap could be synamic in size and we control the lifetime of the data.

fn main () {

fn a () {

let x: &str = "hello";

let y:i32 = 22;

b();

}

fn b() {

let x:String::from("world");

}

}

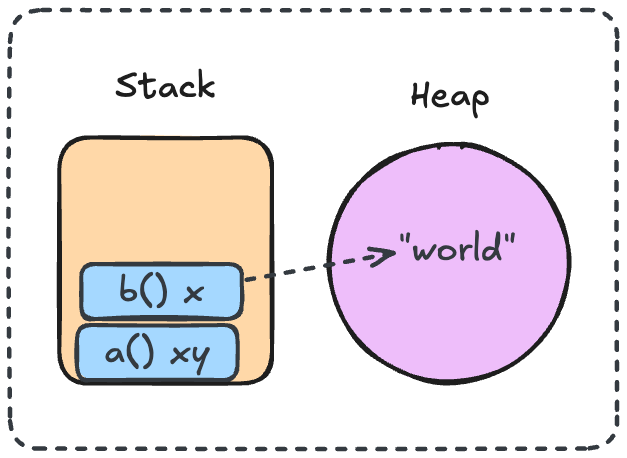

Let's look at this example, In this program, a gets executed first, so we push it onto the stack. Then a also executes b so we also push stack frame for b into the stack.

When b finishes executing, it gets popped off the stack and all of it's variables gets dropped. Same with a , when it gets done executed, it's local variables also gets dropped.

Now let's talk about heap for this program, over here after executing function a, it creates new stack frames and initializes the variables x and y.

Here x is a string literal, which is actually stored in our binary. So in the stack frame, x will be a reference to that string in binary. But y is a i32 bit integer which is a fixed size, so we can store y directly in the stack frame.

When we execute function b, it also creates another stack frame. then b also creates it's own variable named x which is a string type.

As x is string, dynamic in size, we can't really store it directly in stack, so we ask heap to allocate memeory for the string, which heap does.

One thing to note is that pushing to stack is faster than allocating on the heap because the heap has to has to spend time looking for a place to store new data. Accessing data on the stack is faster than heap,because with heap you just need to follow the pointer.

Let's understand some ownership rules:

- Each value in rust has a variable, that's called it's owner.

- There can only be one owner at a time.

- When owner get's out of scope, the value will be dropped.

Normally String literals are directly stored in binary and are fixed in size so stored on stack. But what if we wanted a string dynamic and we can mutate?

let s: String::from ("hello");

Now it will be stored on heap. Let's look into it, so when we declared this string, rust already allocates memory on heap. When scope ends, rust drops our value and de-allocates memory on heap.

How variables and data interact?

let x: i32 = 5

let y: i32 = x; //copy

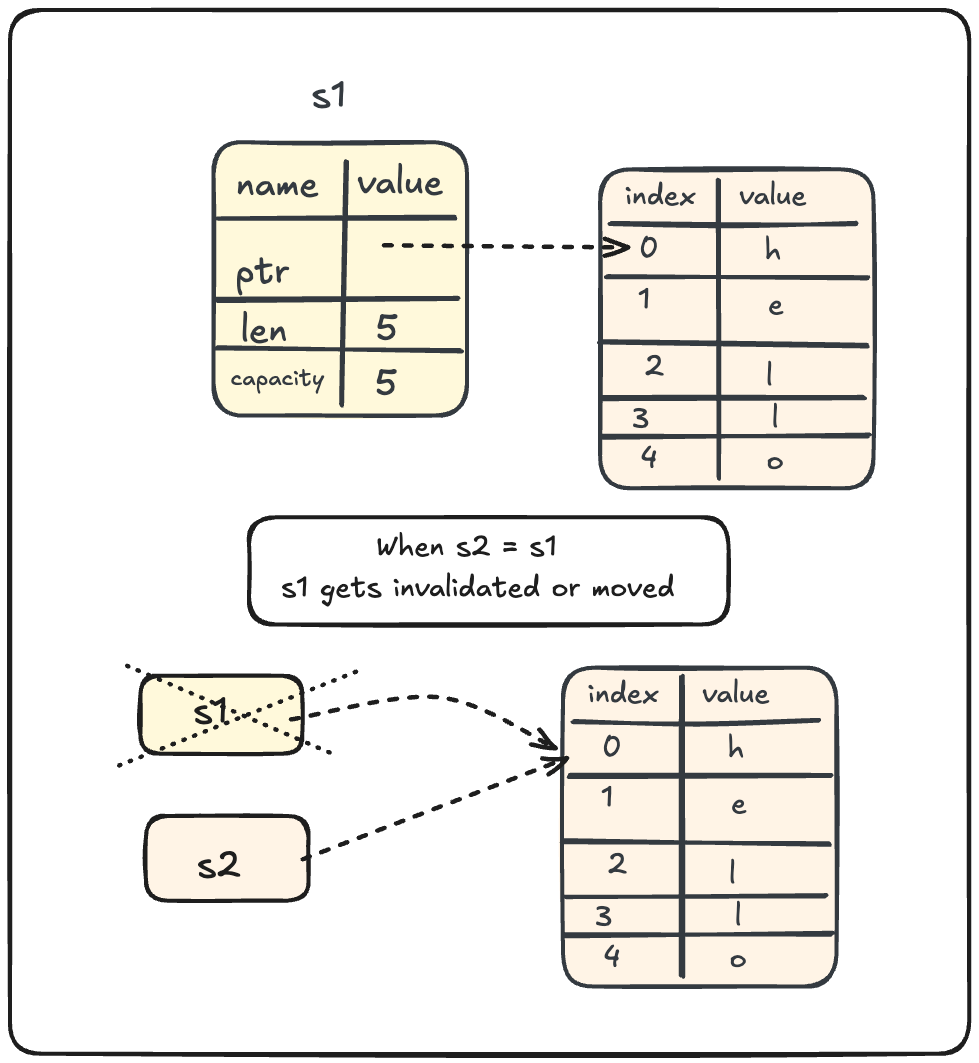

let s1: String = String ::from("hello");

let s2: String = s1;

Here to ensure memory safety, rust invalidates s1, so it moves the value.

Here to ensure meory safety, rust invalidates s1. So it moves the value.

You can also clone let s2: String = s1.clone().

Rust mostly defaults to move but if you want to do more expensive clone then clone().

Rust has copy trait for simple types, stored on stack, such as integers, booleans and characters.

This copy trait allows these types to be copied than move.

If you want to learn more about ownership, head over here.

What if we want to use a variable without taking ownership?

That's where references comes in.

fn main() {

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let len = calculate_length(&s1);

println!("The length of '{s1}' is {len}.");

}

fn calculate_length(s: &String) -> usize {

s.len()

}

Note that we pass &s1 into calculate_length and, in its definition, we take &String rather than String. These ampersands represent references, and they allow you to refer to some value without taking ownership of it

References don't take ownership of the value. For example &String is a reference type. References are immutable by default. We have to make the variable mutable to make the reference mutable.

Some rules of reference:

- At any given time, you can have either one mutable reference or any number of immutable references.

- Reference must always be valid.

Mutable References

We mentioned references are immutable by default. But what if we want to modify borrowed data? We need mutable references.

fn main() {

let mut s = String::from("hello");

change(&mut s);

println!("{s}"); // prints "hello, world"

}

fn change(s: &mut String) {

s.push_str(", world");

}

Notice three things:

- The variable

smust be declared asmut - We pass

&mut s(a mutable reference) - The function accepts

&mut String

All three are required for this to work.

The Big Restriction: You can only have ONE mutable reference to a value in a particular scope. This prevents data races at compile time.

let mut s = String::from("hello");

let r1 = &mut s;

let r2 = &mut s; // ERROR: cannot borrow `s` as mutable more than once

println!("{r1}, {r2}");

You also can't mix mutable and immutable references:

let mut s = String::from("hello");

let r1 = &s; // immutable borrow

let r2 = &s; // fine, multiple immutable borrows allowed

let r3 = &mut s; // ERROR: cannot borrow as mutable because it's also borrowed as immutable

println!("{r1}, {r2}, {r3}");

Dangling References

Rust prevents dangling references (pointers to memory that has been freed). The compiler ensures references are always valid.

fn main() {

let reference_to_nothing = dangle();

}

fn dangle() -> &String { // ERROR!

let s = String::from("hello");

&s // we return a reference to s

} // s goes out of scope and is dropped. Its memory is gone!

The compiler will stop you:

error[E0106]: missing lifetime specifier

The fix? Return the owned value instead:

fn no_dangle() -> String {

let s = String::from("hello");

s // ownership is moved out, nothing is dropped

}

Ownership and Functions

Passing a value to a function moves or copies it, just like assignment.

fn main() {

let s = String::from("hello"); // s comes into scope

takes_ownership(s); // s's value moves into the function

// println!("{s}"); // ERROR: s is no longer valid here

let x = 5; // x comes into scope

makes_copy(x); // i32 is Copy, so x is still valid

println!("{x}"); // This works fine!

}

fn takes_ownership(some_string: String) {

println!("{some_string}");

} // some_string goes out of scope and `drop` is called. Memory freed.

fn makes_copy(some_integer: i32) {

println!("{some_integer}");

} // some_integer goes out of scope. Nothing special happens.

Returning Ownership

Functions can also transfer ownership back:

fn main() {

let s1 = gives_ownership(); // moves return value into s1

let s2 = String::from("hello"); // s2 comes into scope

let s3 = takes_and_gives_back(s2); // s2 is moved into function,

// return value moves into s3

}

fn gives_ownership() -> String {

let some_string = String::from("yours");

some_string // returned and moves out to calling function

}

fn takes_and_gives_back(a_string: String) -> String {

a_string // returned and moves out to calling function

}

This pattern of taking and returning ownership is tedious. That's exactly why Rust has references.

Slice Types

Slices let you reference a contiguous sequence of elements rather than the whole collection. A slice is a kind of reference, so it doesn't have ownership.

String Slices

let s = String::from("hello world");

let hello = &s[0..5]; // "hello"

let world = &s[6..11]; // "world"

The type of a string slice is &str.

Range syntax shortcuts:

let s = String::from("hello");

let slice = &s[0..2]; // "he"

let slice = &s[..2]; // same thing, start from 0

let len = s.len();

let slice = &s[3..len]; // "lo"

let slice = &s[3..]; // same thing, go to end

let slice = &s[..]; // entire string

Why Slices Matter

Consider this function that finds the first word:

fn first_word(s: &String) -> usize {

let bytes = s.as_bytes();

for (i, &item) in bytes.iter().enumerate() {

if item == b' ' {

return i;

}

}

s.len()

}

This returns an index, but there's a problem:

fn main() {

let mut s = String::from("hello world");

let word = first_word(&s); // word = 5

s.clear(); // empties the String

// word is still 5, but s is now ""!

// word is now meaningless and out of sync

}

The index word has no connection to s. With slices, the compiler protects us:

fn first_word(s: &String) -> &str {

let bytes = s.as_bytes();

for (i, &item) in bytes.iter().enumerate() {

if item == b' ' {

return &s[0..i];

}

}

&s[..]

}

fn main() {

let mut s = String::from("hello world");

let word = first_word(&s); // immutable borrow here

s.clear(); // ERROR: cannot borrow `s` as mutable because

// it's also borrowed as immutable

println!("the first word is: {word}");

}

The compiler ensures our slice reference stays valid!

String Literals Are Slices

Remember string literals? They're actually slices:

let s: &str = "Hello, world!";

s is a &str pointing to that specific point in the binary. This is why string literals are immutable—&str is an immutable reference.

Pro tip: Write functions to take &str instead of &String for flexibility:

fn first_word(s: &str) -> &str { // accepts both &String and &str

// ...

}

fn main() {

let my_string = String::from("hello world");

let word = first_word(&my_string[..]); // pass slice of String

let my_literal = "hello world";

let word = first_word(my_literal); // works directly!

}

Array Slices

Slices work on arrays too:

let a = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

let slice = &a[1..3]; // type is &[i32], value is [2, 3]

assert_eq!(slice, &[2, 3]);

This works the same way, slice is a reference to a portion of the array.

Ownership & Borrowing Exercises to Practice

Exercise 1: Move Semantics

Create two String variables where the second is assigned from the first:

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let s2 = s1;

Try to print both. What happens? Fix it using .clone().

Exercise 2: Copy vs Move

Run this code:

let x: i32 = 5;

let y = x;

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let s2 = s1;

println!("{}", x);

println!("{}", s1);

Which line causes an error? Why does x work but s1 doesn't?

Exercise 3: Ownership and Functions

This code doesn't compile:

fn main() {

let message = String::from("hello");

print_message(message);

print_message(message);

}

fn print_message(msg: String) {

println!("{}", msg);

}

Why? Fix it two ways:

- Using

.clone() - By changing the function to take a reference

Exercise 4: Returning Ownership

Write a function create_greeting(name: &str) -> String that returns "Hello, {name}!".

Call it and print the result. Who owns the returned String — the function or the caller?

Exercise 5: References

Write a function count_words(text: &String) -> usize that returns how many words are in the text (split by whitespace).

Call it twice on the same string:

let text = String::from("the quick brown fox");

println!("{}", count_words(&text));

println!("{}", count_words(&text)); // should work — why?

Hint: Use .split_whitespace().count()

Exercise 6: Mutable References

Write a function add_exclamation(text: &mut String) that appends "!" to the string.

Test it:

let mut msg = String::from("Hello");

add_exclamation(&mut msg);

println!("{}", msg); // should print "Hello!"

What three things must be mut for this to work?

Exercise 7: Borrowing Rules

This code breaks a borrowing rule:

let mut s = String::from("hello");

let r1 = &s;

let r2 = &s;

let r3 = &mut s;

println!("{}, {}, {}", r1, r2, r3);

What rule does it break? Fix it by rearranging (not removing) lines.

Hint: References are only active until their last use.

Exercise 8: Mutable Reference Restriction

This also breaks a rule:

let mut s = String::from("hello");

let r1 = &mut s;

let r2 = &mut s;

println!("{}, {}", r1, r2);

What's the rule? Fix it so both mutations can happen (sequentially, not simultaneously).

Exercise 9: Dangling Reference

This function won't compile:

fn create_string() -> &String {

let s = String::from("hello");

&s

}

Why? What happens to s when the function ends?

Fix it by returning an owned String instead of a reference.

Exercise 10: String Slices

Create a String and practice slice syntax:

let s = String::from("hello world");

// Create slices for:

// 1. "hello" (first 5 characters)

// 2. "world" (last 5 characters)

// 3. "llo wo" (middle portion)

// 4. The entire string using [..]

What is the type of each slice?

Exercise 11: Why Slices Matter

This compiles but has a bug:

fn first_word_index(s: &String) -> usize {

for (i, &byte) in s.as_bytes().iter().enumerate() {

if byte == b' ' {

return i;

}

}

s.len()

}

fn main() {

let mut s = String::from("hello world");

let word_end = first_word_index(&s);

s.clear();

println!("First word ends at: {}", word_end); // word_end is now meaningless!

}

Rewrite first_word_index to return &str instead of usize. Name it first_word.

After your change, what happens when you try to call s.clear() before using the slice?

Exercise 12: Flexible Function Parameters

Write a function is_empty_or_whitespace(s: &str) -> bool that returns true if the string is empty or contains only spaces.

Test it with both a String and a string literal:

let owned = String::from(" ");

let literal = "hello";

println!("{}", is_empty_or_whitespace(&owned)); // true

println!("{}", is_empty_or_whitespace(literal)); // false

Why is &str more flexible than &String for the parameter type?

Hint: Use .trim().is_empty()