Smart Pointers in Rust

December 29, 2025Part 1: Understanding Memory First

Before smart pointers make sense, you need to understand where your data lives.

The Stack

The stack is like a stack of books on your desk. You can only add books to the top, and only remove from the top. This is called LIFO, Last In, First Out.

fn main() {

let a = 5; // Put 5 on the stack

let b = true; // Put true on top

let c = 'x'; // Put 'x' on top

} // Everything is removed in reverse order: c, b, a

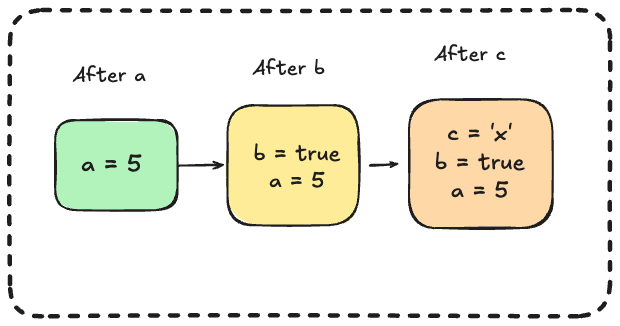

Visual of the stack:

Stack is:

- Super fast (just moving a pointer up and down)

- Automatically cleaned up when functions end

- But size must be known at compile time

- Limited space (usually a few MB)

The Heap

The heap is like a warehouse. You can store things anywhere there's space. You get a ticket (address) telling you where your stuff is.

fn main() {

// The actual text "hello" is stored in the warehouse (heap)

// s holds the ticket (pointer) to find it

let s = String::from("hello");

}

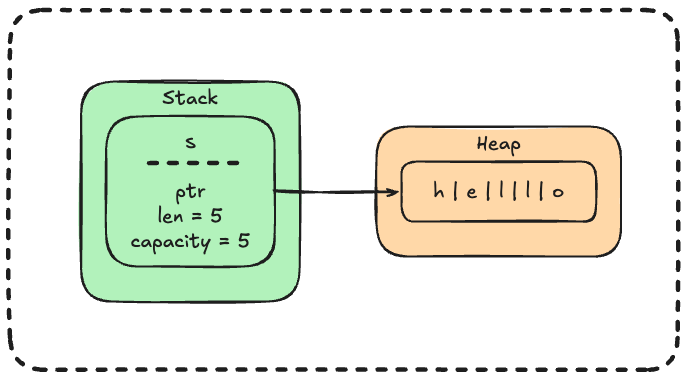

Visual:

Heap is:

- Slower (need to search for space, follow pointers)

- You control when things get cleaned up

- Size can be decided while program runs

- Much larger space available

Why Does This Matter?

Smart pointers give you control over heap allocation. They let you:

- Put data on the heap when you need to

- Share heap data between multiple parts of your program

- Manage when heap data gets cleaned up automatically

What Is a Pointer?

A pointer is just an address. It tells you WHERE something is, not WHAT it is.

fn main() {

let age = 25;

let pointer_to_age = &age; // This holds the ADDRESS of age

println!("The address is: {:p}", pointer_to_age);

println!("The value at that address is: {}", *pointer_to_age);

}

Output might look like:

The address is: 0x7ffd5e8c3a4c

The value at that address is: 25

Analogy:

ageis your housepointer_to_ageis a piece of paper with your home address written on it

The paper isn't your house, it just tells you where to find it.

What Makes a Pointer "Smart"?

A regular pointer (like &age) just holds an address. That's all it does.

A smart pointer is smarter because it:

- Holds an address (like a regular pointer)

- Has extra information (metadata)

- Does helpful things automatically (like cleanup)

- Usually owns the data it points to

The most important "extra thing" is automatic cleanup. When a smart pointer is done being used, it cleans up the data it points to. No manual memory management needed!

Key traits that make a pointer "smart":

| Trait | What It Does |

|---|---|

Deref |

Lets you use * to get the inner data |

Drop |

Runs cleanup code when the pointer goes out of scope |

Secret: You've already used smart pointers!

fn main() {

let s = String::from("hello"); // String is a smart pointer!

let v = vec![1, 2, 3]; // Vec is a smart pointer!

}

String points to heap-allocated text and automatically frees it when done. That's smart pointer behavior!

Part 2: Box<T>: The Simplest Smart Pointer

What Is Box?

Box does one simple thing: puts your data on the heap instead of the stack.

That's it. No fancy features. Just: "put this on the heap and give me a pointer to it."

Basic Usage

fn main() {

// Without Box: 5 lives on the stack

let a = 5;

// With Box: 5 lives on the heap

let b = Box::new(5);

println!("a = {}", a);

println!("b = {}", b); // You can use b just like a regular number!

}

Output:

a = 5

b = 5

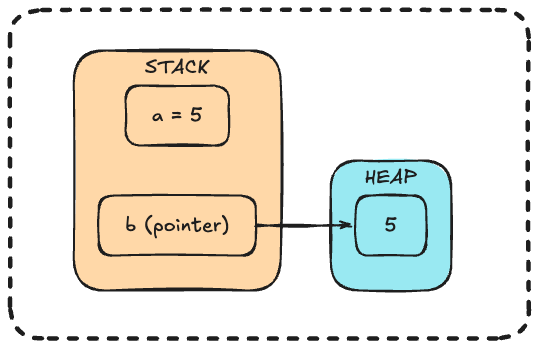

What's happening in memory:

a(the number 5) is directly on the stackbis a pointer on the stack, pointing to the number 5 on the heap

Using a Box

You can use a Box almost exactly like the regular value:

fn main() {

let boxed = Box::new(10);

// Reading the value

println!("Value is: {}", boxed);

// Doing math (need * to get the actual number)

let doubled = *boxed * 2;

println!("Doubled: {}", doubled);

}

The * means "go get the value this points to." This is called dereferencing.

Changing the Value Inside

fn main() {

let mut boxed = Box::new(5);

println!("Before: {}", boxed);

*boxed = 10; // Change what's in the box

println!("After: {}", boxed);

*boxed += 5; // Add 5 to it

println!("Final: {}", boxed);

}

Output:

Before: 5

After: 10

Final: 15

Automatic Cleanup

When a Box goes away, it automatically cleans up the heap memory:

fn main() {

{

let boxed = Box::new(100);

println!("Inside: {}", boxed);

} // boxed is gone here, heap memory is automatically freed!

println!("Outside the block now");

}

You don't have to do anything, Box cleans up after itself. That's what makes it smart!

Why Would You Use Box?

Reason 1: Recursive Types (The Most Important Reason)

This is where Box becomes essential, not optional.

Imagine you want to make a chain of numbers, like a linked list:

1 → 2 → 3 → end

You might try:

// THIS WON'T WORK!

enum Chain {

Link(i32, Chain), // A link has a number and another chain

End,

}

Rust says: Error! This type has infinite size!

Why? Rust needs to know the size of every type at compile time. Let's think about how big Chain is:

Endis small (no data)Linkhas a number (4 bytes) plus anotherChain- But that

Chainmight be aLinkwith anotherChain - Which might be a

Linkwith anotherChain... - Forever!

It's like asking: "How big is a box that contains itself?" There's no answer!

Size of Chain = 4 bytes + Size of Chain

= 4 bytes + 4 bytes + Size of Chain

= 4 bytes + 4 bytes + 4 bytes + Size of Chain

= infinity!

The Fix: Use Box

Instead of storing a Chain directly, store a pointer to a Chain. A pointer has a fixed, known size (8 bytes).

enum Chain {

Link(i32, Box<Chain>), // A link has a number and a POINTER to another chain

End,

}

fn main() {

// Build: 1 → 2 → 3 → End

let chain = Chain::Link(

1,

Box::new(Chain::Link(

2,

Box::new(Chain::Link(

3,

Box::new(Chain::End)

))

))

);

println!("Chain created!");

}

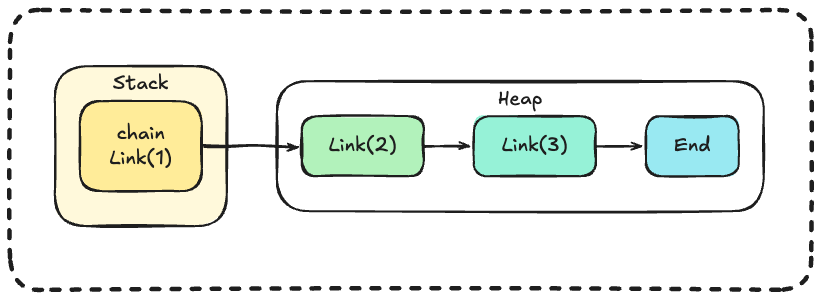

Now the size is known:

End: smallLink: 4 bytes (number) + 8 bytes (pointer) = 12 bytes

A pointer always has the same size, no matter what it points to!

Memory layout:

Reason 2: Large Data Transfer

When you pass data to a function, Rust copies it. For large data, this is slow:

fn main() {

// This array is 1 million bytes!

let huge_array = [0u8; 1_000_000];

// This copies all 1 million bytes, slow!

process(huge_array);

}

fn process(data: [u8; 1_000_000]) {

println!("Got {} bytes", data.len());

}

With Box, only the pointer (8 bytes) is copied:

fn main() {

let huge_array = Box::new([0u8; 1_000_000]);

// This only copies the 8-byte pointer, fast!

process(huge_array);

}

fn process(data: Box<[u8; 1_000_000]>) {

println!("Got {} bytes", data.len());

}

When to Use Box: Summary

| Situation | Use Box? | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Recursive types (lists, trees) | Yes, required | Breaks infinite size problem |

| Large data you want to transfer | Yes | Only copies the pointer |

| Small, simple data | No | Stack is faster |

| You need multiple owners | No | Use Rc instead |

Part 3: The Deref Trait: Acting Like a Regular Value

What Is Dereferencing?

When you have a pointer, dereferencing means "follow the pointer and get the value."

fn main() {

let x = 5;

let pointer = &x;

// pointer holds an address

// *pointer follows the address to get 5

println!("x = {}", x);

println!("*pointer = {}", *pointer);

}

Analogy:

pointeris like a slip of paper that says "your package is in locker 1000"*pointeris like going to locker 1000 and getting your package

Box Supports Dereferencing

Because Box implements the Deref trait, you can use * on it:

fn main() {

let x = 5;

let y = Box::new(x); // y is a Box containing 5

println!("x = {}", x);

println!("*y = {}", *y); // Follow the pointer to get 5

// These are equal

assert_eq!(x, *y);

}

Rust Often Dereferences For You

Thanks to Deref, Rust is often smart enough to dereference automatically:

fn main() {

let boxed = Box::new(String::from("hello"));

// All of these work:

println!("{}", boxed); // Rust dereferences automatically

println!("{}", *boxed); // Explicit dereference

println!("Length: {}", boxed.len()); // Methods work too!

}

Deref Coercion: Automatic Type Conversion

This is a convenience feature. Rust will automatically convert types through the deref chain:

fn say_hello(name: &str) {

println!("Hello, {}!", name);

}

fn main() {

let boxed_string = Box::new(String::from("World"));

// say_hello wants &str

// We have Box<String>

// Rust automatically converts: &Box<String> → &String → &str

say_hello(&boxed_string);

}

Output:

Hello, World!

How it works:

We have: &Box<String>

Function wants: &str

Step 1: Box<String> derefs to String

So &Box<String> becomes &String

Step 2: String derefs to str

So &String becomes &str

Result: &Box<String> → &String → &str ✓

Rust does this at compile time with zero runtime cost. You don't need to understand all the details, just know that Rust helpfully converts types when it can!

Part 4: The Drop Trait: Automatic Cleanup

What Is Drop?

The Drop trait lets you run code when something is about to be thrown away (goes out of scope).

struct Noisy {

name: String,

}

impl Drop for Noisy {

fn drop(&mut self) {

println!("{} is being dropped!", self.name);

}

}

fn main() {

let a = Noisy { name: String::from("first") };

let b = Noisy { name: String::from("second") };

println!("End of main");

}

Output:

End of main

second is being dropped!

first is being dropped!

Key observation: Things are dropped in reverse order, last created, first dropped.

Why Reverse Order?

This is intentional. Later values might depend on earlier values. If we dropped a first but b still needed a, we'd have a problem!

By dropping in reverse order, dependencies are always valid when something is dropped.

Why Drop Matters

This is how Box (and other smart pointers) clean up heap memory automatically:

- You create a

Box::new(5), Rust allocates memory on the heap - You use the Box normally

- Box goes out of scope

- Rust calls the Box's

dropmethod - The

dropmethod frees the heap memory

You never have to think about it. No memory leaks, no manual free() calls!

Dropping Early

Normally things are dropped at the end of their scope. But you can drop something early using drop():

fn main() {

let x = String::from("hello");

println!("x exists: {}", x);

drop(x); // x is dropped RIGHT HERE

println!("x is gone now");

// println!("{}", x); // ERROR! x doesn't exist anymore

}

When would you want this?

Example: Releasing a lock early so others can use the resource:

fn main() {

let lock = acquire_lock("database");

// Do critical work

println!("Working with database...");

drop(lock); // Release the lock now, not at end of function

// Do other work that doesn't need the database

println!("Doing other things...");

}

Without drop(lock), the database would stay locked until the end of the function.

Part 5: Rc<T>: Multiple Owners

The Problem: Single Ownership

In Rust, every value has ONE owner. When the owner goes away, the value is dropped.

But what if two things need to share the same data?

fn main() {

let data = String::from("shared");

let a = data; // data moves to a

let b = data; // ERROR! data was already moved

}

You might think cloning works:

fn main() {

let data = String::from("shared");

let a = data.clone(); // Makes a complete copy

let b = data.clone(); // Makes another complete copy

// But now we have 3 SEPARATE strings, not shared data!

}

Now changes to one don't affect the others. They're independent copies.

The Analogy: Library Books

Think of a library book:

- Multiple people can borrow the same book

- The book stays in the library as long as someone has it

- When the last person returns it, the library can remove it

Rc works like this. Multiple "owners" can share the same data. The data is only freed when ALL owners are done with it.

Basic Rc Usage

Rc stands for Reference Counting. It tracks how many owners exist.

use std::rc::Rc;

fn main() {

// Create shared data

let shared = Rc::new(String::from("hello"));

// Create more owners (this is cheap!)

let owner_a = Rc::clone(&shared);

let owner_b = Rc::clone(&shared);

// All three point to the SAME string

println!("shared: {}", shared);

println!("owner_a: {}", owner_a);

println!("owner_b: {}", owner_b);

}

Output:

shared: hello

owner_a: hello

owner_b: hello

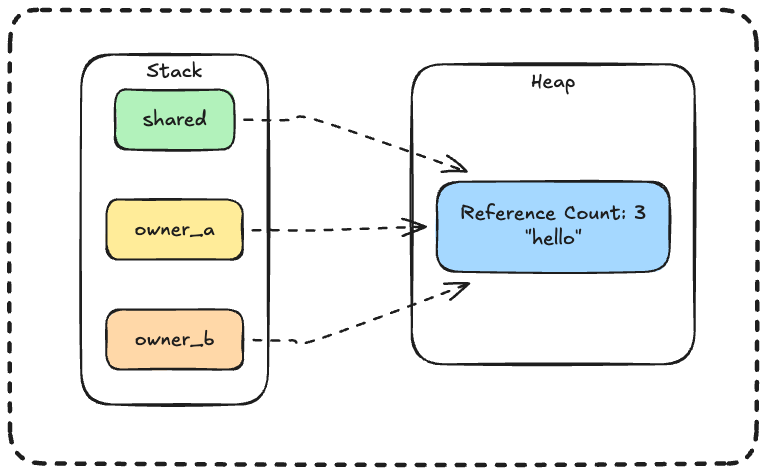

Memory layout:

All three variables point to the same heap allocation!

Watching the Reference Count

use std::rc::Rc;

fn main() {

let a = Rc::new(5);

println!("Count: {}", Rc::strong_count(&a)); // 1

let b = Rc::clone(&a);

println!("Count: {}", Rc::strong_count(&a)); // 2

{

let c = Rc::clone(&a);

println!("Count: {}", Rc::strong_count(&a)); // 3

} // c is dropped here

println!("Count: {}", Rc::strong_count(&a)); // 2

}

Output:

Count: 1

Count: 2

Count: 3

Count: 2

When the count reaches 0 (when the last owner goes away), the data is freed.

Rc::clone Is Cheap!

Important: Rc::clone does NOT copy the data. It just:

- Increments the reference count (adds 1 to a number)

- Copies the pointer (8 bytes)

use std::rc::Rc;

fn main() {

// Even if this string was a million characters

let big_data = Rc::new(String::from("imagine a huge string here"));

// This is instant, just adds 1 to a counter

let clone1 = Rc::clone(&big_data);

let clone2 = Rc::clone(&big_data);

// All three point to the SAME data in memory

}

| Operation | What It Does | Speed |

|---|---|---|

String::clone() |

Copies all character data | Slow for large strings |

Rc::clone() |

Just increments counter | Always instant |

Convention: We write Rc::clone(&x) instead of x.clone() to make it obvious this is a cheap reference clone, not an expensive data copy.

Critical Limitation: Rc Is Read-Only

You cannot change data through an Rc:

use std::rc::Rc;

fn main() {

let data = Rc::new(5);

// *data = 10; // ERROR! Can't change it

}

Why? Think about it: if multiple parts of your code share data, and any of them could change it at any time, you'd have chaos. One part changes the data, another part is surprised by the change, bugs happen!

Rust prevents this by making Rc data immutable.

But what if you need shared data that can change? That's where RefCell comes in...

Part 6: RefCell<T>: Interior Mutability

The Problem: Compile-Time Rules Are Too Strict

Rust's borrowing rules are checked at compile time:

- You can have many

&T(immutable references), OR - You can have one

&mut T(mutable reference) - Never both at the same time

These rules prevent bugs and keep Rust safe. But sometimes you KNOW your code is safe, even if the compiler can't prove it.

RefCell: Runtime Checking Instead

RefCell lets you bend the rules. Instead of compile-time checking, it checks at runtime.

use std::cell::RefCell;

fn main() {

// Note: NOT declared as mut!

let data = RefCell::new(5);

// Read the value

println!("Value: {}", *data.borrow());

// Change the value

*data.borrow_mut() = 10;

println!("New value: {}", *data.borrow());

}

Output:

Value: 5

New value: 10

Wait, what? data isn't declared as mut, but we still changed it!

This is interior mutability. The RefCell wrapper provides mutability internally.

How RefCell Works

| Method | What It Returns | Like |

|---|---|---|

data.borrow() |

Read access | &data |

data.borrow_mut() |

Write access | &mut data |

| Regular References | RefCell |

|---|---|

| Checked at compile time | Checked at runtime |

| Zero runtime cost | Small runtime cost |

| Compile errors for violations | Panics for violations |

The Rules Still Apply!

The borrowing rules still apply, they're just checked when your program runs.

Multiple immutable borrows: OK

use std::cell::RefCell;

fn main() {

let data = RefCell::new(5);

let r1 = data.borrow();

let r2 = data.borrow();

println!("{} {}", *r1, *r2); // Works fine!

}

Mutable borrow while immutable exists: PANIC

use std::cell::RefCell;

fn main() {

let data = RefCell::new(5);

let r1 = data.borrow(); // Immutable borrow

let w1 = data.borrow_mut(); // PANIC! Already borrowed

}

This crashes at runtime:

thread 'main' panicked at 'already borrowed: BorrowMutError'

Multiple mutable borrows: PANIC

use std::cell::RefCell;

fn main() {

let data = RefCell::new(5);

let w1 = data.borrow_mut();

let w2 = data.borrow_mut(); // PANIC! Already mutably borrowed

}

When the Borrow Ends

Borrows from RefCell end when the returned value is dropped:

use std::cell::RefCell;

fn main() {

let data = RefCell::new(5);

{

let mut borrow = data.borrow_mut();

*borrow = 10;

} // borrow is dropped here, releasing the mutable borrow

// Now we can borrow again

println!("Value: {}", *data.borrow());

}

When Would You Use RefCell?

The most common case: you want to change something inside a method that takes &self:

use std::cell::RefCell;

struct Counter {

count: RefCell<i32>,

}

impl Counter {

fn new() -> Counter {

Counter { count: RefCell::new(0) }

}

fn increment(&self) { // Note: &self, not &mut self!

*self.count.borrow_mut() += 1;

}

fn get(&self) -> i32 {

*self.count.borrow()

}

}

fn main() {

let counter = Counter::new(); // Not mut!

counter.increment();

counter.increment();

counter.increment();

println!("Count: {}", counter.get());

}

Output:

Count: 3

We updated the count even though we only had &self!

Part 7: Combining Rc and RefCell

Now the powerful combination:

Rc= multiple owners of the same dataRefCell= can change the value

Together: multiple owners who can ALL change the shared data!

Basic Example

use std::cell::RefCell;

use std::rc::Rc;

fn main() {

// Shared, changeable number

let shared = Rc::new(RefCell::new(0));

// Create multiple owners

let a = Rc::clone(&shared);

let b = Rc::clone(&shared);

// a changes the value

*a.borrow_mut() += 10;

println!("After a adds 10: {}", shared.borrow());

// b changes the value

*b.borrow_mut() += 5;

println!("After b adds 5: {}", shared.borrow());

// Original sees all changes

println!("Final value: {}", shared.borrow());

}

Output:

After a adds 10: 10

After b adds 5: 15

Final value: 15

All three (shared, a, b) see the same value because they all point to the same data!

Practical Example: Shared Score

use std::cell::RefCell;

use std::rc::Rc;

fn main() {

// A score that multiple players can change

let score = Rc::new(RefCell::new(0));

// Player 1's reference

let player1_score = Rc::clone(&score);

// Player 2's reference

let player2_score = Rc::clone(&score);

// Player 1 scores

*player1_score.borrow_mut() += 10;

println!("Player 1 scored! Total: {}", score.borrow());

// Player 2 scores

*player2_score.borrow_mut() += 20;

println!("Player 2 scored! Total: {}", score.borrow());

// Player 1 scores again

*player1_score.borrow_mut() += 15;

println!("Player 1 scored! Total: {}", score.borrow());

}

Output:

Player 1 scored! Total: 10

Player 2 scored! Total: 30

Player 1 scored! Total: 45

Both players affect the same score!

Part 8: Reference Cycles and Memory Leaks

The Problem: Rc Can Leak Memory

Rc frees memory when the reference count reaches 0. But what if the count can NEVER reach zero?

Imagine:

- A points to B (B's count = 1)

- B points to A (A's count = 1)

- We stop using both from outside

- A's count is still 1 (B holds it)

- B's count is still 1 (A holds it)

- Neither can ever be freed!

┌─────────┐

▼ │

A ──────► B

This is a reference cycle, and it causes a memory leak.

Simple Example of a Cycle

use std::cell::RefCell;

use std::rc::Rc;

struct Node {

next: RefCell<Option<Rc<Node>>>,

}

fn main() {

let a = Rc::new(Node { next: RefCell::new(None) });

let b = Rc::new(Node { next: RefCell::new(Some(Rc::clone(&a))) });

// b points to a. Count: a=2, b=1

// Now make a point to b, creating a cycle!

*a.next.borrow_mut() = Some(Rc::clone(&b));

// Count: a=2, b=2

// When function ends:

// - Drop a: count goes 2→1 (b still holds it)

// - Drop b: count goes 2→1 (a still holds it)

// - Neither reaches 0. Memory leak!

}

The Solution: Weak References

Rc has two types of references:

| Type | Created With | Keeps Data Alive? |

|---|---|---|

| Strong | Rc::clone(&rc) |

Yes |

| Weak | Rc::downgrade(&rc) |

No |

A weak reference says "I want to know if this value exists, but I don't want to prevent it from being dropped."

use std::rc::{Rc, Weak};

fn main() {

let strong = Rc::new(5);

println!("Strong count: {}", Rc::strong_count(&strong)); // 1

// Create a weak reference

let weak: Weak<i32> = Rc::downgrade(&strong);

println!("Strong count: {}", Rc::strong_count(&strong)); // Still 1!

// Weak references don't increase the count

}

Using Weak References

Since a weak reference doesn't keep data alive, the data might be gone! You have to check with upgrade():

use std::rc::{Rc, Weak};

fn main() {

let strong = Rc::new(5);

let weak = Rc::downgrade(&strong);

// upgrade() returns Some if data exists, None if it's gone

match weak.upgrade() {

Some(value) => println!("Value exists: {}", value),

None => println!("Value is gone!"),

}

// Drop the strong reference

drop(strong);

// Now the data is gone

match weak.upgrade() {

Some(value) => println!("Value exists: {}", value),

None => println!("Value is gone!"),

}

}

Output:

Value exists: 5

Value is gone!

Breaking Cycles with Weak

The rule: use strong references for things you own, weak references for back-references.

Common pattern:

- Parents have strong references to children (parent owns children)

- Children have weak references to parents (child can access parent, but doesn't own it)

use std::rc::{Rc, Weak};

use std::cell::RefCell;

struct Node {

value: i32,

parent: RefCell<Weak<Node>>, // Weak! Doesn't own parent

child: RefCell<Option<Rc<Node>>>, // Strong! Owns child

}

Why this works:

- When parent goes out of scope, its strong count drops to 0

- Parent is dropped, which drops its child reference

- Child's strong count drops

- When child's count reaches 0, it's dropped too

- All memory is freed properly!

The weak reference from child to parent doesn't prevent the parent from being dropped.

Summary: Which One Do I Use?

Quick Decision Guide

Do you need heap allocation?

├── No → Use regular variables

└── Yes → Continue...

│

├── Do you need multiple owners?

│ ├── No → Use Box<T>

│ └── Yes → Use Rc<T>

│

└── Do you need to change the value?

├── Through a mutable variable → Box<T> with mut

└── Through an immutable reference → RefCell<T>

Do you need multiple owners AND changing?

└── Yes → Use Rc<RefCell<T>>

Do you have a cycle (A points to B, B points to A)?

└── Yes → Use Weak<T> for one direction

The Complete Table

| Smart Pointer | Owners | Can Change? | Use For |

|---|---|---|---|

Box<T> |

One | If variable is mut | Heap data, recursive types |

Rc<T> |

Many | No | Sharing read-only data |

RefCell<T> |

One | Yes (runtime checked) | Changing through &self |

Rc<RefCell<T>> |

Many | Yes (runtime checked) | Sharing changeable data |

Weak<T> |

Zero (doesn't own) | N/A | Breaking cycles |

Key Traits

| Trait | Purpose |

|---|---|

Deref |

Lets you use *x to get inner value |

DerefMut |

Lets you use *x = value to change inner value |

Drop |

Runs cleanup code when value goes out of scope |